Famine No More?

The recent crisis in the Horn of Africa — so reminiscent of the 1980s — may suggest that fighting famine is futile. But better tools, heavier hitters, and the benefits of child sponsorship are saving lives.

By James Addis

Photos by Jon Warren

Caption

Isnino Siyat made it to Dadaab, a refugee camp in Kenya, with her husband and two children after walking for 10 days from their village in Somalia. She said the drought “finished both our livestock and our farm,” killing their five cows and 10 goats one by one over three months. Reaching Dadaab, Isnino was exhausted but had to make her own hut out of sticks, borrowed clothing scraps, and burlap sacks that once contained relief food. She worked alone while her husband was elsewhere in the camp, preparing for burial the body of their 3-year-old nephew, who died on the journey.

The first televised images of famine in 1984, showing thousands of starving children in Ethiopia, sent shockwaves throughout the world. Among those who reacted were rock stars. Bob Geldof organized fellow British performers to record the hit fundraising single “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” that inspired USA for Africa musicians to release the best-selling song “We Are the World.”

Bob Geldof was in the news again last September as a new famine deepened in the Horn of Africa, threatening some 13 million lives. Sir Bob pressed delegates attending the United Nations General Assembly in New York to sign a charter drafted by a coalition of aid agencies, including World Vision, asking for key commitments from world leaders to prevent future hunger disasters.

The resurfacing of Bob Geldof in this context prompts inevitable questions: Why is this happening again? What progress has been made over the last 25 years to prevent these kinds of catastrophic events?

All the rock-star fundraisers in the world could not prevent the dire drought that gripped the Horn last year. But today there are new tools enabling the international community to predict and mitigate such a disaster. And a key point of progress is child sponsorship.

In drought-affected areas where World Vision works, communities proved themselves resilient, and none of the nearly 250,000 sponsored children succumbed to starvation.

Caption

Men in Dadaab camp attended to the grim task of preparing a child’s grave — the third child buried that day. Three-year-old Ibrahim had trekked from Somalia to Kenya with his family, but like many children, he arrived hungry, weak, and sick, and he died at the camp clinic. Nearby, other graves, marked by earthen mounds of varying sizes, represented the toll of Somalia’s crisis.

Caption

There was little privacy or protection in the makeshift home that Hadija Hassan Abdi, 28, constructed for herself and her seven children at the Burtinle camp in Puntland, Somalia. The family left Baidoa after the maize crop failed in 2011. They walked and hitched rides for eight days, begging for food as they went. Once at the camp, Hadija and her eldest daughter, 10-year-old Nurto, earned a little money by hauling garbage away for families in nearby Burtinle city.

Arming and Alarming

One outcome of the 1980s famine in Ethiopia is the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), funded by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) — the U.S. government’s foreign aid arm.

FEWS NET monitors changes in climate to predict adverse events like drought and uses satellites to analyze agricultural production in famine-prone regions. At the same time, on-the-ground monitoring looks closely at food prices in local markets. “Alarm bells ring as soon as food prices begin to rise,” says David Scheiman, director of World Vision’s Africa programs.

The collection of such data is greatly facilitated by the surprisingly good cellphone coverage that now exists in much of Africa — technology that was unknown in the ’80s.

David is fond of recounting the story of Joseph in the Bible, who correctly interpreted Pharaoh’s dream indicating seven years of famine in Egypt. Armed with this information, Joseph proposed a plan to successfully withstand the calamity. “Similarly, with better information,” David says, “humanitarian organizations like World Vision can take more effective preventative measures against famine than ever before.”

USAID Administrator Dr. Raj Shah agrees, pointing out that FEWS NET indicated high risk in August 2010. “By September and October, we were able to provide early allocations of food security assistance to set up and work with a range of partners,” he says, “and to supplement some of the larger safety-net programs for [livestock-dependant] communities.”

Those safety-net programs, he adds, deserve the credit for keeping millions of people from starvation.

Therapeutic feeding products are a primary means of helping acutely malnourished children. One of the most exciting to emerge in recent years is Plumpy’nut — a peanut-based therapeutic food that requires no preparation or mixing with water. Parents can take the ready-to-eat packets home for their children. Plumpy’nut works fast and well. “I’ve personally seen children — little more than skeletons at death’s door — return to good health in weeks,” David says.

Caption

Layla, a young mother of five children — and pregnant with her sixth — fled from Mogadishu to a camp in Garowe, Somalia, some 600 miles away. Her youngest, 18-month-old Zam Zam, arrived severely malnourished, a condition immediately recognizable to health workers. Happily, just weeks later, World Vision staff observed great improvement in Zam Zam as a result of therapeutic feeding.

Why Famine Happened

Even with better tools, no one could stop the drought emergency from escalating in Somalia into full-blown famine — the first in the 21st century. Why? David Scheiman and others note that this was the worst drought in 60 years, even more severe and widespread than the one that struck Ethiopia in the 1980s. Experts also point to climactic factors. Meteorologists have shown that mean temperatures in East Africa have risen by more than two degrees Fahrenheit in recent years. At the same time, rainfall has decreased. The combination makes growing crops more difficult and therefore tends to diminish available food supplies.

Drought-fueled hunger is a slow-onset emergency, which doesn’t always prompt quick action — even, some criticize, from the United Nations and Horn of Africa governments themselves. Aid organizations like World Vision often have difficulty focusing supporters’ attention on hunger, especially compared to more sudden, headline-grabbing crises such as tsunamis, floods, or earthquakes (see “Hunger Isn’t News,” page 20).

For example, following Japan’s major earthquake in March 2011, World Vision donors gave more than $59 million in just three months to support relief efforts there. By contrast, it took five months to raise $50 million for the Horn — only half the amount needed for ongoing relief in the region.

It’s important to note that even in the driest regions of Kenya and Ethiopia, drought did not develop into famine, which is declared when at least 20 percent of the population lacks basic food, global acute malnutrition exceeds 30 percent, and more than two people per 10,000 die daily. Improvements in those countries over the past decades, as well as stable governments, helped prevent the worst from happening.

The same cannot be said for hard-hit Somalia, where drought was exacerbated by political turmoil.

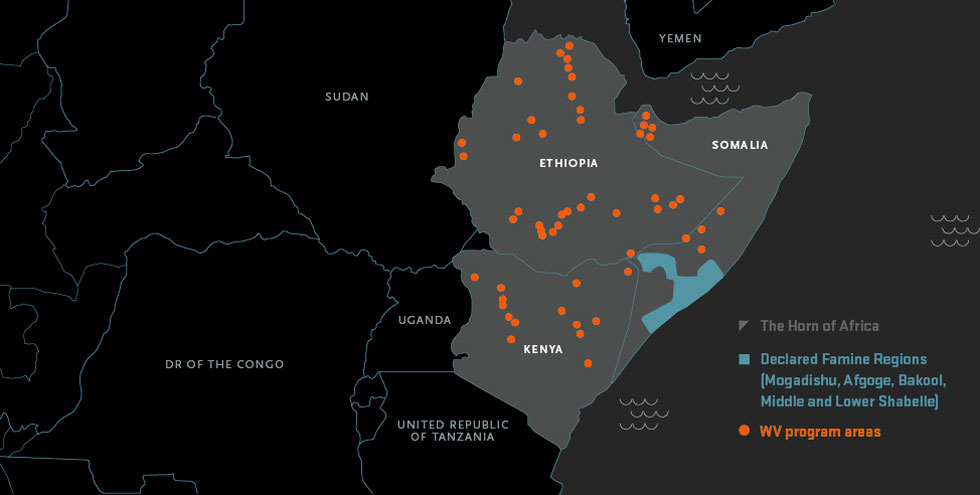

In August 2010, militants expelled World Vision and more than a dozen other aid organizations from the south-central regions of the country. According to Chris Smoot, World Vision’s director of programs for Somalia, this invited further tragedy. At the time of World Vision’s expulsion, FEWS NET maps showed yellow (stressed) in places where World Vision operated. These areas were surrounded by a sea of red (emergency).

“We knew things were going to get bad,” Chris says. “We just did not know the extent of how bad it was going to be.”

The answer turned out to be very bad indeed. Dr. Raj Shah says the militants' actions helped contribute to this famine that has taken the lives of tens of thousands of children. Lack of food, water, and humanitarian assistance forced hundreds of thousands of Somalis, mainly women and children, to flee to overcrowded refugee camps in neighboring Ethiopia and Kenya, often facing robbery and sexual assault on the way.

Caption

Although devastated by drought, families in Wajir South, Kenya, remained in their homes rather than fleeing to refugee camps. They pointed to World Vision as the reason for their stability: Starting in December 2010, the organization trucked in emergency water and distributed five gallons twice a week to each family. “The water sustains our life,” said an elderly pastoralist, who noted that the past four years had been the longest stretch without rain he had ever experienced.

The First Response

The crisis prompted World Vision to declare a top-priority emergency in February 2011 and mount a massive relief effort in four countries — Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, and Somalia. (Although excluded from south-central Somalia, the organization remained in Puntland and Somaliland in the north.)

Ongoing programs across the region include supplying tents and medical care to refugees, trucking water into dry areas, providing seeds and animal feed, and initiating emergency feeding for starving children and hungry adults, especially new mothers.

World Vision also runs school feeding programs, which encourage children to stay in school and ensure they get at least one good meal every day. By July 2011, more than 1 million people were benefiting from World Vision’s relief operations in the Horn.

Thinking outside the box has helped. Conventional wisdom calls for importing food into famine-hit countries. But in Kenya, World Vision tested the idea that there was sufficient supply and infrastructure available to procure food from areas of surplus within the country. This enabled the prompt feeding of more than 3,000 vulnerable families in Moyale, northern Kenya. Food arrived within weeks, not the four months that is typical for such emergency relief. Acute malnutrition rates in Moyale were kept down to less than 14 percent, whereas in surrounding areas they exceeded 20 percent.

World Vision’s emphasis on child and maternal health in sponsorship-supported communities means malnutrition problems can be spotted early or prevented entirely. In recent years, the organization has refined an approach known as the “7-11 strategy” — seven basic steps to ensure the health and nutrition of pregnant moms and 11 steps to protect the health and nutrition of newborns. By paying attention to simple things like hand washing, breastfeeding, and vaccination, thousands of lives are being saved.

Such programs have been difficult in Somalia, says Chris Smoot, in part because nearly all of World Vision’s work there is funded by Western-government grants. These grants are critical for saving lives but relatively inflexible without matching private donations. They operate for a limited time, and money cannot be easily redirected to cope with changing priorities.

Contrast this with child-sponsorship funding in Kenya, Ethiopia, and Tanzania. (Due to Somalia’s instability, sponsorship is not possible there.) Sponsorship provides an investment in communities for 15 years or more, allowing World Vision to design long-term programs that address the needs of families in holistic ways. And if the need arises, funds can be spent to address urgent problems in those communities.

A good example is in Wajir South, eastern Kenya, where rains failed completely in 2010, and all water points dried up. As is customary in World Vision’s sponsorship model, community leaders approached Jacob Alemu, who leads the project in Wajir, saying, “You are our only hope as to whether we die or whether we live.”

In response, Jacob activated his emergency budget in December 2010, and World Vision started bringing in water by truck, first using government vehicles, then taking over the whole operation to serve 7,000 households. “Nobody died because of lack of water,” he says. Water trucking continued until October 2011, when the rains came.

Caption

In Puntland, a region of Somalia less affected by conflict and drought, World Vision provided medical care and children’s health monitoring in remote villages. Here in Magacley, Anas Abdullai Fahar brought her feverish 2-year-old grandson, Mohamed, to Dr. Said Owar Husen, who measured the boy’s arm circumference and diagnosed him as malnourished. Such care has made a difference — malnutrition rates here are less than 20 percent, well below the national average.

What Works

Many of World Vision’s development programs in Kenya are located in arid or semi-arid regions. Lawrence Kiguro, associate director of livelihoods and resiliency for World Vision in Kenya, says work to combat the effects of drought started in earnest in 2005 following several consecutive seasons of crop failure.

These efforts are legion. They include introducing communities to rainwater-harvesting technologies, drought-resistant crops, hardier goat breeds, and more. These methods are being replicated in more than 60 sponsorship-funded development programs in Ethiopia, serving almost 200,000 sponsored children.

Granted, these are mammoth tasks — not just to establish the programs, but also to educate local people on how to implement the new ideas and convince them of the benefits. But based on experiences so far, Lawrence remains confident that the effects of drought can be beaten. “I am sure we can protect communities if we continue to expand successful initiatives in new areas,” he says.

Lawrence points to World Vision’s standout project, the Morulem Irrigation Scheme in Turkana, Kenya, constructed with a combination of USAID grants and child sponsorship funding. The project uses a network of canals to direct water from the Kerio River to irrigate 1,500 acres of land, supporting more than 3,000 families. At a time when the food situation in other parts of Turkana has reached crisis levels, farms in Morulem are flourishing with maize, sorghum, and a variety of fruits and vegetables.

Morulem’s children are healthy and active. “We eat every day, and we never go hungry,” says Loice Akaran, 11. “I am able to concentrate in school.”

Tree planting is another method showing extraordinary promise in arid regions. Trees retain moisture and nutrients in the soil, inhibit soil erosion, and improve the climate. In fact, experts at the Center for International Forestry Research claim that forest destruction has done more than drought to turn vast areas of once grazeable and farmable land into “lunar-like” landscapes.

But this process can be reversed. An example is a joint World Vision/World Bank program in Ethiopia’s Humbo district, which suffered massive forest clearing in the mid-1970s. Through the rehabilitation of 2,700 hectares of forest, the program has drastically reduced soil erosion, improved pasture, reduced temperatures, and increased rainfall — not to mention provided income for the local community through the use of tree products.

Transformational programs like those in Humbo and Morulem prove that when sponsorship funding is leveraged by grants from strong partners, hunger emergencies can be prevented, despite environmental factors beyond our control. “Droughts will always be with us,” says Charles Owubah, World Vision’s regional director in Africa. “But, truly, children do not have to die.”

And those who have been provided the safety net of child sponsorship in the Horn of Africa are not dying. Sponsors’ support not only improves the lives of individual children but also helps make their communities better able to withstand the worst in times of disaster.

Famine-fighting is not in World Vision’s purview alone; the organization works alongside a vast array of humanitarian, government, and nongovernmental groups to provide long-term development assistance in the Horn of Africa. Collectively, these efforts raise hope that famine’s tragedy will not recur.

“We know how to do this,” declares Dr. Raj Shah. “It’s just a matter of getting the world together to get it done.” •